Skaergaard history

Name

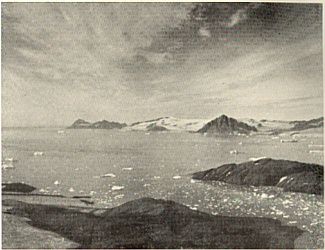

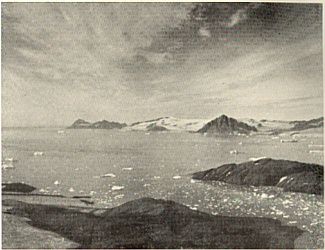

In its Danish spelling, Skærgård, is the official name of the

area. Skaergaard, the internationalised version, is a geological formation

name, referring to the intrusion itself. Skærgård is a Scandinavian

word for a rocky coastline protected by numerous off-lying islands

and skerries, where the sea merges with the land via an anastamosing system

of fjord-like channels. Such coastlines are common around Scandinavia,

especially along the Swedish and Finnish Baltic coasts, and by comparison

that at Kangerlussuaq is very modest, covering only a tiny area.

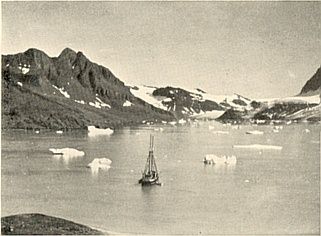

The name was applied however by the members of the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition

in 1900 (Amdrup, 1902), who travelled the approximately 800 kilometres

from near the present day Scoresby Sund (Ittoqqortoormiit) southwards to

Ammassalik (Tasiilaq) in an open rowing boat and who were, so far as is

known, the first Europeans to visit the area. To these travellers, after

rowing 400 kilometres through drifting polar pack ice along the black,

inhospitable basalt cliffs of the Blosseville Kyst (= Coast), Skærgård

with its numerous small, rounded islands of warm brown (Fe-rich) gabbro

and pale Archaean country rock gneisses, the large open fjord of Kangerlusuaq,

must have seemed like a new land.

"Skærgård" does not appear to be used by the local Eskimo

or Inuit people who live semi-permanently in the area. Instead, it is referred

to as Kangerlussuaq (Kangerdlugssuaq in the earlier orthography, used in

the geological literature), which means "Big Fjord", a name which occurs

very frequently throughout Greenland (e.g. Søndre Strømfjord,

the main traffic centre and former US. military air base on the West coast,

is also Kangerlussuaq).

[Place names of the Kangerlussuaq area]

History of indigenous settlement

These

Europeans - of the Amdrup-Hartz expedition, or even unknown European whalers

who may have landed here earlier without leaving a record - were by no

means the first people in this area. Indeed, Kangerlussuaq was a milepost

for the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition because it marked the northernmost point

known to the Ammassalik people (Ammassalimiut) as told to their discoverer

Gustav Holm in 1882 (Gustav Holm, 1888, 1889). Although no people lived

in the area at the turn of the century, numerous ruins of earlier dwellings

testify to the previous presence of the Inuit people. Indeed, an old man,

Kunak, told Gustav Holm that he had been born on the nearby island of Nordre

Aputitêq ( - new spelling: Apulileeq) and had travelled to Kangerlussuaq

in his youth. Material returned by the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition was described

by W. Thalbitzer (1909, see also Thalbitzer, 1914) and excavations on the

house ruins at Skærgård and in Miki Fjord where made by the

Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition in 1932 (Mathiassen,

1934; Degerbøl, 1934) and the Anglo-Danish East Greenland Expedition

of 1935 (Larsen, 1938). Since 1935 only minor archaeological work has been

carried out, in spite of the fact that revolutionary changes have taken

place in the field of Eskimo archaeology.

These

Europeans - of the Amdrup-Hartz expedition, or even unknown European whalers

who may have landed here earlier without leaving a record - were by no

means the first people in this area. Indeed, Kangerlussuaq was a milepost

for the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition because it marked the northernmost point

known to the Ammassalik people (Ammassalimiut) as told to their discoverer

Gustav Holm in 1882 (Gustav Holm, 1888, 1889). Although no people lived

in the area at the turn of the century, numerous ruins of earlier dwellings

testify to the previous presence of the Inuit people. Indeed, an old man,

Kunak, told Gustav Holm that he had been born on the nearby island of Nordre

Aputitêq ( - new spelling: Apulileeq) and had travelled to Kangerlussuaq

in his youth. Material returned by the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition was described

by W. Thalbitzer (1909, see also Thalbitzer, 1914) and excavations on the

house ruins at Skærgård and in Miki Fjord where made by the

Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition in 1932 (Mathiassen,

1934; Degerbøl, 1934) and the Anglo-Danish East Greenland Expedition

of 1935 (Larsen, 1938). Since 1935 only minor archaeological work has been

carried out, in spite of the fact that revolutionary changes have taken

place in the field of Eskimo archaeology.

The reason for the extinction of the Inuit people shortly prior to the

arrival of Europeans is unclear but must be related to the general depopulation

of the entire East Greenland area during the last century. Authorities

have been divided on whether the population came to Kangerlussuaq from

the north or the south but all agreed that their dwellings date from the

period around the late 13th century to the early 19th century. Degerbøl

(1934) recognized three types of ruin: a sunken type with rounded corners

and a short entrance passage; a longhouse similar to those of Ammassalik

but otherwise unknown further northwards and small houses built within

the earlier longhouses and featuring long entrance passages. Since the

1930s, Eskimo archaeology has advanced considerably and we now know that

the settlement of Greenland had begun more than 4000 years ago by the so-called

"Palaeo-eskimos". Some objects in the earlier collections from Kangerlussuaq

are of undoubted Palaeo-eskimo origin (Kapel, 1990) and new investigations

are now required in the light of greatly improved archaeological techniques

and vastly extended knowledge - the Palaeo-eskimos were unknown at the

time of the earlier excavations. During a reconnaissance in connection

with the projected gold mine it was found that some of the sites had been

vandalized, although many are still untouched either by vandals or archaeologists

- a further argument for renewed archaeological work.

To

the Ammassalik people, Kangerlussuaq apparently has always been regarded

as an especially rich hunting ground - a kind of Shangri-La, that can be

reached only with difficulty but where life can be expected to be good.

At the time of Gustav Holm, an umiak or family boat left Ammassalik

for Kangerlussuaq, but was never heard of again, and this expedition was

probably the origin of the corpses found in the house at Nugalik or Dødemandspynten

(="Dead Man's Point"), about 100 km to the south, found by Amdrup some

30 years later (Amdrup, 1902). The Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East

Greenland Expedition was largely motivated by the expressed desire of the

Ammassalik people to colonize Kangerlussuaq. Ammassalik people still regard

the area with high esteem: some as pragmatists who realize that they can

apply their hunting skills here with the prospect of improving their income,

others as idealists who see the area as a retreat from the white man's

world to the ways of their forefathers, untrammelled by money, stores,

officials, drunkenness and the like.

To

the Ammassalik people, Kangerlussuaq apparently has always been regarded

as an especially rich hunting ground - a kind of Shangri-La, that can be

reached only with difficulty but where life can be expected to be good.

At the time of Gustav Holm, an umiak or family boat left Ammassalik

for Kangerlussuaq, but was never heard of again, and this expedition was

probably the origin of the corpses found in the house at Nugalik or Dødemandspynten

(="Dead Man's Point"), about 100 km to the south, found by Amdrup some

30 years later (Amdrup, 1902). The Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East

Greenland Expedition was largely motivated by the expressed desire of the

Ammassalik people to colonize Kangerlussuaq. Ammassalik people still regard

the area with high esteem: some as pragmatists who realize that they can

apply their hunting skills here with the prospect of improving their income,

others as idealists who see the area as a retreat from the white man's

world to the ways of their forefathers, untrammelled by money, stores,

officials, drunkenness and the like.

In 1947, twenty five people from Ammassalik moved to Kangerlussuaq,

but found the hunting poor and were forced to return. According to Underbjerg

(1984) this was possibly because the weather station was located on Skærgårdhalvø

at this time and he speculates that perhaps one of the reasons for moving

it to Nordre Aputitêq was to improve the hunting conditions around

Skærgård.

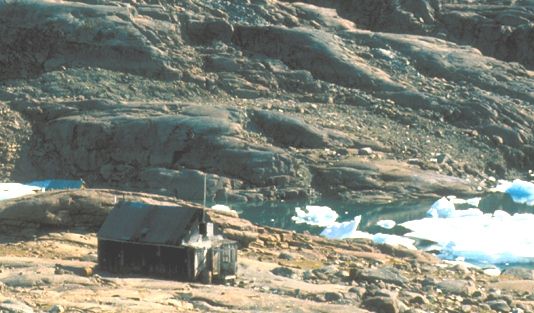

Recent

endeavours to colonize Kangerlussuaq date from 1966 when a number of families

from Ammassalik (Tasiilaq) overwintered in the remains of the old American

weather station and the expedition houses from the 30s. They had a very

good season (- 35 bears, 62 narwhales and about 2100 seals) and returned

most years afterwards. Not surprisingly, many from Ammassalik find life

at Kangerlussuaq difficult and yearn for home, but others return year after

year. An excellent study of present social conditions among the Ammassalimiut

has been presented by Robert-Lamblin (1986), who recorded the numbers of

hunters at various sites along the coast up to 1979. In recent years the

number of people living at Kangerlussuaq was: 56(20) in 1986-87 (after

a hiatus of three years), 94(37) in 1987-88, 39 (16) in 1988-89, 0 in 1989-90

and 18(9) in 1990-91. In each case the first number is the total number

of individuals and the second (in brackets) the number of children under

16 years. Figures are based on data from Tasiilaq local council.

Recent

endeavours to colonize Kangerlussuaq date from 1966 when a number of families

from Ammassalik (Tasiilaq) overwintered in the remains of the old American

weather station and the expedition houses from the 30s. They had a very

good season (- 35 bears, 62 narwhales and about 2100 seals) and returned

most years afterwards. Not surprisingly, many from Ammassalik find life

at Kangerlussuaq difficult and yearn for home, but others return year after

year. An excellent study of present social conditions among the Ammassalimiut

has been presented by Robert-Lamblin (1986), who recorded the numbers of

hunters at various sites along the coast up to 1979. In recent years the

number of people living at Kangerlussuaq was: 56(20) in 1986-87 (after

a hiatus of three years), 94(37) in 1987-88, 39 (16) in 1988-89, 0 in 1989-90

and 18(9) in 1990-91. In each case the first number is the total number

of individuals and the second (in brackets) the number of children under

16 years. Figures are based on data from Tasiilaq local council.

The 1930s and 1940s

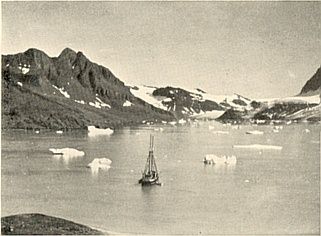

Wager discovered the Skaergaard Intrusion during a brief foray by ship

during the British Arctic Air Route Expedition (BAARE) in 1930. This expedition

overwintered at Supertooq, which is just west of Sermilik Fjord in the

Ammassalik District. It was notable in that it made use of some of the

first aircraft to be employed in Greenland: two De Havilland "Gypsy Moths".

Thus oblique aerial photographs of high quality were available for field

work, and examples were published in the Skaergaard Memoir (Wager &

Deer, 1939) and subsequent works. Unfortunately, the negatives are no longer

serviceable due to poor storage conditions. The BAARE expedition was described

in the book Northern Lights by F. Spencer Chapman (Chapman, 1932)

while an official report appeared in the Geographical Journal (Watkins,

1932a & b) to which Wager contributed a geological summary (see also

Watkins, 1932c).

Wager's

first visit to Skaergaard was of necessity brief, but he returned in 1932

as a member of the Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition

in 1932 (Mikkelsen,1933a & b). This committee had been formed to promote

the establishment of a settlement at Scoresby Sund (now Ittoqqortoormiit)

to relieve the population pressure at Ammassalik and in 1925 (as a result

of their first expedition) this settlement became a reality (Mikkelsen,

1927). The 1932 expedition was designed to explore the coastline

between Ammassalik and Scoresbysund and to erect houses at strategic points

along the coast, with a view to promoting travel between the two areas

and to explore the possibility for colonizing the Kangerlussuaq area. Although

the expedition was successful, its ultimate aim has never been fulfilled:

no journeys have ever been made by Inuit along the entire length of this

coast and no permanent settlement was ever established, although overwintering

parties have been at Skaergaard most years since 1966 (see above).

Wager's

first visit to Skaergaard was of necessity brief, but he returned in 1932

as a member of the Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition

in 1932 (Mikkelsen,1933a & b). This committee had been formed to promote

the establishment of a settlement at Scoresby Sund (now Ittoqqortoormiit)

to relieve the population pressure at Ammassalik and in 1925 (as a result

of their first expedition) this settlement became a reality (Mikkelsen,

1927). The 1932 expedition was designed to explore the coastline

between Ammassalik and Scoresbysund and to erect houses at strategic points

along the coast, with a view to promoting travel between the two areas

and to explore the possibility for colonizing the Kangerlussuaq area. Although

the expedition was successful, its ultimate aim has never been fulfilled:

no journeys have ever been made by Inuit along the entire length of this

coast and no permanent settlement was ever established, although overwintering

parties have been at Skaergaard most years since 1966 (see above).

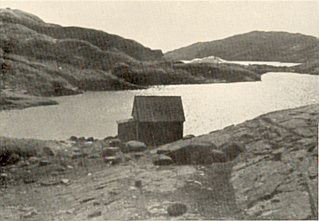

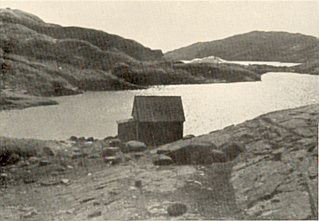

During his two first expeditions, Wager had made remarkable strides

in elucidating the previously unknown geology of the immense area (perhaps

as much as 100,000 km2) between Ammassalik and Scoresby Sund

(Wager, 1934), but he was convinced that Skaergaard was worthy of detailed

study. With this as a primary goal, he returned in 1935 with a small party,

including his brother (a botanist), their two wives, W.A. Deer (a geologist),

a medical doctor and a general assistant, together with a party of two

Inuit families, forming the British East Greenland Expedition, 1935-1936

(Wager, 1937). They overwintered in a small house which they constructed

on what they called "Home Bay" (now Hjemsted Bugt), and they also used

two houses that had been erected by the Mikkelsen expedition in 1932. All

these houses, along with a further one built by Mikkelsen at Miki Fjord

(shown on Wager and Deer's Skaergaard map) have since been destroyed, although

they were in good condition until the late 1960s.

Up to this time, the only geologist other than Wager and Deer, who had

seen the Skaergaard was S.R.F.Bøgvad who stopped briefly during

the Seventh Thule Expedition in 1932 (see: Gabel-Jørgensen, 1935

& 1940, also Spender, 1934, for descriptive accounts of this expedition).

Bøgvad did not however publish his findings, and, because his notes

where written in code, all his observations were effectively lost on his

death.

Weather stations and older commercial activity

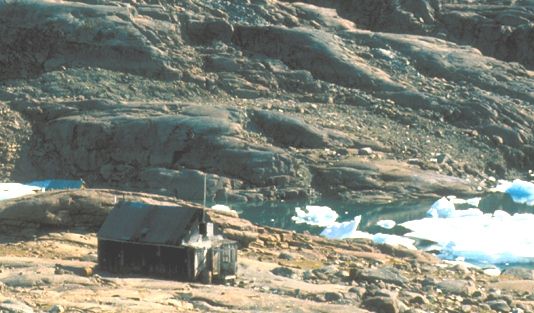

In 1945, because of World War II , the United States established a weather

station at the site of the present hunting settlement on Skærgårdshalvø.

Remains of this station can still be seen, but by 1966, none of the structures

remained standing. In 1949 the station was transferred to Nordre Apulileeq

(= Aputitêq), about 45 km to the southwest, probably because the

weather at the original site was deemed to be too local.

A

long-standing Norwegian interest in the area led to the establishment of

a radio station, known as "Storfjord Radio", at Mudderbugt on the west

side of Kangerlussuaq (which is known to Norwegians as "Storfjord", the

Scandinavian translation of the Greenlandic name) as part of the International

Polar Year. This station operated through 1932-33 and remains can still

be seen. Several small huts were also erected around the fjord: at Spækpynten,

Bagnæsset and Skåret (on Kræmer Ø), for use by

sealers and shark fishers from Ålesund and Tromsø, but falling

prices for animal oils, the main product of this industry, led to their

abandonment in the 1950s. The characteristic wooden ships (Signalhorn,

Furenak, Brandal, Polarbjørn) which were mostly built around

the turn of the century, have now disappeared from the area, but their

immense strength and the unparalleled skill of their skippers in these

treacherous waters meant that a few of them were still in demand as expedition

ships and supply vessels for the weather stations such as Nordre Apulileeq

(= Aputitêq), where seven men lived totally isolated except for the

yearly ship. Many Skaergaard geologists will remember the cheerful stewards

on these ships, with their filling Norwegian food, after a summer on meagre

expedition rations. They will similarly remember how the ships, built for

shunting ice, rolled in the autumn swell of the Denmark Strait and how

quickly the desire to visit the mess-room disappeared. These ships are

now all gone. Commercial sealing has virtually ceased due to the pressures

of the environmental lobby; geologists now fly and the weather station

at Nordre Apulileeq was closed in 1979 due to financial restrictions and

the introduction of automatic, telemetred weather reporting. Since that

time, the once luxurious facilities at the station have fallen into a ruinous

condition. Until recently the only ship visiting Skaergaard was Ejnar Mikkelsen,

the local boat from Ammassalik, chartered by the municipality (Tasiilaq

Kommune) to transport the hunters, their families, dogs and equipment.

Its skipper, Hans Ignatiussen, was a son of one of the couples who pioneered

the present overwintering parties at Skaergaard. However, in connection

with mineral exploration (see below), Icelandic boats (including an old

roll-on-roll-off car ferry) have been chartered in recent years to deliver

fuel for diamond drilling and helicopters and the Ejnar Mikkelsen is no

more, having been destroyed by the ice in the winter of 1993.

A

long-standing Norwegian interest in the area led to the establishment of

a radio station, known as "Storfjord Radio", at Mudderbugt on the west

side of Kangerlussuaq (which is known to Norwegians as "Storfjord", the

Scandinavian translation of the Greenlandic name) as part of the International

Polar Year. This station operated through 1932-33 and remains can still

be seen. Several small huts were also erected around the fjord: at Spækpynten,

Bagnæsset and Skåret (on Kræmer Ø), for use by

sealers and shark fishers from Ålesund and Tromsø, but falling

prices for animal oils, the main product of this industry, led to their

abandonment in the 1950s. The characteristic wooden ships (Signalhorn,

Furenak, Brandal, Polarbjørn) which were mostly built around

the turn of the century, have now disappeared from the area, but their

immense strength and the unparalleled skill of their skippers in these

treacherous waters meant that a few of them were still in demand as expedition

ships and supply vessels for the weather stations such as Nordre Apulileeq

(= Aputitêq), where seven men lived totally isolated except for the

yearly ship. Many Skaergaard geologists will remember the cheerful stewards

on these ships, with their filling Norwegian food, after a summer on meagre

expedition rations. They will similarly remember how the ships, built for

shunting ice, rolled in the autumn swell of the Denmark Strait and how

quickly the desire to visit the mess-room disappeared. These ships are

now all gone. Commercial sealing has virtually ceased due to the pressures

of the environmental lobby; geologists now fly and the weather station

at Nordre Apulileeq was closed in 1979 due to financial restrictions and

the introduction of automatic, telemetred weather reporting. Since that

time, the once luxurious facilities at the station have fallen into a ruinous

condition. Until recently the only ship visiting Skaergaard was Ejnar Mikkelsen,

the local boat from Ammassalik, chartered by the municipality (Tasiilaq

Kommune) to transport the hunters, their families, dogs and equipment.

Its skipper, Hans Ignatiussen, was a son of one of the couples who pioneered

the present overwintering parties at Skaergaard. However, in connection

with mineral exploration (see below), Icelandic boats (including an old

roll-on-roll-off car ferry) have been chartered in recent years to deliver

fuel for diamond drilling and helicopters and the Ejnar Mikkelsen is no

more, having been destroyed by the ice in the winter of 1993.

Geological work in the period 1950 to 1970

After Wager and Deer's epic overwintering in 1935-36, there was a hiatus

caused by the war and no geologist visited the area until 1953. By this

time, it had become apparent that new field observations were necessary

and, in addition, many of the original specimens had been consumed through

mineral separation and wet chemical analysis (this was, of course, before

the days of the electron microprobe and other non-destructive analytical

methods). The 1953 British East Greenland Geological Expedition consisted

of L.R. Wager (leader), W.A. Deer, G.M. Brown, P.E. Brown, C.J. Hughes

and G.D. Nicholls was mounted (Wager,1954). Its objectives were to make

new collections from Skaergaard, to examine and map critical areas of the

intrusion and to work on other geological features of the immediate neighbourhood,

such as the layered gabbros of Kap Edvard Holm and the Kangerdlugssuaq

alkaline intrusion. The expedition travelled by chartered Norwegian sealer

and was a success, even though it was very modestly funded - there are

stories of Wager sweeping up rice, etc. from the floor of the hut when

the ship was delayed and rations were exhausted.

After

1953, another long hiatus in field work ensued, but during this period

a large amount of laboratory work was published, dealing especially with

the geochemistry of numerous trace elements. Apart from a brief visit by

J.A.V.Douglas in 1962, no geologist came to Skaergaard again until 1966,

when there was a new British East Greenland Geological Expedition (Deer,

1967). The main purpose of this expedition was to sample the intrusion

by several diamond drill holes: a deep hole in the Hidden Zone and several

shorter holes specifically aimed at studying sedimentation phenomena in

the exposed layered series. In addition, several of the other Tertiary

intrusive centres were to be explored, notably the Kappa Edward Hole, and

Lilies areas. The impetus for deep drilling came from the "MO hole"

project: Wager had been to California, attending a meeting of the International

Mineralogical Association, where there was a session on layered intrusions.

This was the time of the ill-fated "MO hole" project, while a plan was

also afoot to drill the Muskox intrusion by the Geological Survey of Canada

(realized in 1964) and Wager came to consider the possibility of using

a drilling barge at Skaergaard. This turned out to be impractical, but

it sparked the interest in drilling and an expedition was planned to extend

over two years. However, when Wager died in the later part of 1965, while

heavily involved in preparations for the expedition, the leadership passed

to W.A.Deer and for various reasons the project was shortened to only one

year. The sedimentation study had been Wager's special interest and no-one

was forthcoming with sufficient enthusiasm to take it over and it was dropped.

Also, the original drilling plan for the Hidden Zone proved too ambitious

without considerably escalating the cost of the expedition. Thus after

a 349 m hole had been drilled at a site on the eastern shore of Uttentals

Sund, starting in the lowest part of the Lower Zone, a second hole of 150

m was drilled at another site on the shore just south of Forbindelsesgletscher,

penetrating into the Triple Group. The drill used was a Longyear 35 and

core recovery was very high. Several additional holes were drilled to 45

m along a single stratigraphic interval using a "Packsack" drill with a

motorized hoist, and about two dozen holes, 5 m deep were drilled in the

Trough Bands with a "Dinky" drill. In all 588 m (1930 feet) of core were

recovered and has since been stored at the Department of Earth Sciences

in Cambridge. Up until the present time, the only studies which have been

made of this material were by Maaløe (1974, 1976, 1978, 1987), Nwe

(1975, 1976) and Nwe & Copely (1975). The drilling programme did not

really live up to expectations in that only about 150 m of the Hidden Zone

were penetrated (according to Wager's estimates it is as much as 5 km in

thickness) owing to the loss of water from the drill at this depth and

indications that the hole was passing out of the intrusion. The sedimentation

study visualized by Wager was not carried out, although drill cores for

this purpose were obtained. It was ironic that the major hole into the

Triple Group penetrated to the stratigraphic zone that was later identified

as being gold-bearing, but presence of this zone was not realized at the

time.

After

1953, another long hiatus in field work ensued, but during this period

a large amount of laboratory work was published, dealing especially with

the geochemistry of numerous trace elements. Apart from a brief visit by

J.A.V.Douglas in 1962, no geologist came to Skaergaard again until 1966,

when there was a new British East Greenland Geological Expedition (Deer,

1967). The main purpose of this expedition was to sample the intrusion

by several diamond drill holes: a deep hole in the Hidden Zone and several

shorter holes specifically aimed at studying sedimentation phenomena in

the exposed layered series. In addition, several of the other Tertiary

intrusive centres were to be explored, notably the Kappa Edward Hole, and

Lilies areas. The impetus for deep drilling came from the "MO hole"

project: Wager had been to California, attending a meeting of the International

Mineralogical Association, where there was a session on layered intrusions.

This was the time of the ill-fated "MO hole" project, while a plan was

also afoot to drill the Muskox intrusion by the Geological Survey of Canada

(realized in 1964) and Wager came to consider the possibility of using

a drilling barge at Skaergaard. This turned out to be impractical, but

it sparked the interest in drilling and an expedition was planned to extend

over two years. However, when Wager died in the later part of 1965, while

heavily involved in preparations for the expedition, the leadership passed

to W.A.Deer and for various reasons the project was shortened to only one

year. The sedimentation study had been Wager's special interest and no-one

was forthcoming with sufficient enthusiasm to take it over and it was dropped.

Also, the original drilling plan for the Hidden Zone proved too ambitious

without considerably escalating the cost of the expedition. Thus after

a 349 m hole had been drilled at a site on the eastern shore of Uttentals

Sund, starting in the lowest part of the Lower Zone, a second hole of 150

m was drilled at another site on the shore just south of Forbindelsesgletscher,

penetrating into the Triple Group. The drill used was a Longyear 35 and

core recovery was very high. Several additional holes were drilled to 45

m along a single stratigraphic interval using a "Packsack" drill with a

motorized hoist, and about two dozen holes, 5 m deep were drilled in the

Trough Bands with a "Dinky" drill. In all 588 m (1930 feet) of core were

recovered and has since been stored at the Department of Earth Sciences

in Cambridge. Up until the present time, the only studies which have been

made of this material were by Maaløe (1974, 1976, 1978, 1987), Nwe

(1975, 1976) and Nwe & Copely (1975). The drilling programme did not

really live up to expectations in that only about 150 m of the Hidden Zone

were penetrated (according to Wager's estimates it is as much as 5 km in

thickness) owing to the loss of water from the drill at this depth and

indications that the hole was passing out of the intrusion. The sedimentation

study visualized by Wager was not carried out, although drill cores for

this purpose were obtained. It was ironic that the major hole into the

Triple Group penetrated to the stratigraphic zone that was later identified

as being gold-bearing, but presence of this zone was not realized at the

time.

The 1970s and 1980s

With the death of Wager, a man remarkable in many ways (see Deer,

1967), British interest in Skaergaard to lapsed. In 1970 and 1971 prospectors

from the Northern Mining Company (Nordisk Mineselskab A/S) worked in the

area (Brooks, 1972) and in 1971 an American Expedition led by A.R. McBirney

began further scientific studies of the Skaergaard intrusion. The McBirney

expedition was the first of several, with scientists returning in 1974,

1979, 1985 during this period. Some of the participants who have published

their work were: Leslie C. Coleman, E. Julius Dasch, Gordon G. Goles, James

D. Hoover, T. Neil Irvine, William P. Leeman, H. Richard Naslund,

William H. Taubeneck, Hugh P. Taylor, Jr., Willem Verwoerdt and C.M. White.

H.R. Blank and M.E. Gettings carried out gravity and magnetic surveys that

defined the sub-surface form of the intrusion and aerial photography and

ground control was completed leading to the publication of a topographic

map by the Danish Geodetic Institute (subsequently “Kort og Matrikelstyrelsen,

Danmark”) in 1975. These expeditions have led to a new burst of publications

on Skaergaard, which, combined with new ways of thinking about layered

intrusions in general, is still continuing. In particular, Naslund and

Irvine have been especially active and have subsequently returned on independently

on a number of occasions. The topographic map referred to above led subsequently

to the publication of a geological map (by the University of Oregon) by

McBirney with contributions from J.D.Hoover (Marginal Border Series), M.A.

Kays (metamorohic basement) and Troels Nielsen (Tertiary volcanic and sedimentary

rocks) in !989. A slightly revised edition with petrofabric lineations

by Adolphe Nicolas was published in the book on layered intrusions edited

by Cawthorn.

At the same time (i.e. 1971), the University of Copenhagen under the

leadership of C.K. Brooks began a series of expeditions to the area (in

the years from 1972 to 1991, 1978 and 1983 to 1986 excepted) but the object

of this work was largely regional, designed to elucidate the magmatic,

sedimentological and tectonic features of this important, if not unique,

passive continental margin, of which Skaergaard is a part. Personnel on

these expeditions at various times came from the Universities at Copenhagen,

Århus, Sheffield, Arizona, Stanford, Toronto and Oregon, along with

two geologists from the Northern Mining Company in 1982, whose specific,

interest was the Flammefjeld porphyry molybdenum deposit on the west side

of Kangerlussuaq. (Geyti & Thomassen,1984), which had been discovered

by Brooks & Thomassen in 1970.

In the years 1977 and 1978, the area was visited by the Geological Survey

of Greenland, involved in regional mapping under the leadership of David

Bridgwater (Myers et al. 1979) and, in 1986, two geologists (H-K.Schønwandt

and C.K.Brooks) with two assistants visited the area for the Geological

Survey with a view to appraising the economic mineral resources (Brooks

et al., 1987). They worked in close collaboration with the Geodetic

Institute of Denmark, led by T.I. Hauge Andersson, which was involved in

a detailed survey of the area using Transit and GPS measurements, as well

as gravity measurements. In preparation for this project, two geodecists

visited the area in 1982 along with the University of Copenhagen party

and established the air strip in Sødalen, which was first used the

same year. In 1985, a hut at Sødalen was erected, with funding from

the Geodetic Institute and the University of Toronto and, in 1991, a second,

larger hut was erected by Platinova Resources Ltd. nearby.

Other groups vital to Skaergaard research must also be mentioned: University

of Arizona/Stanford University and Platinova Resources Limited of Toronto.

The Arizona/Stanford work began with an expedition consisting of Denis

Norton and Dennis K. Bird in 1981 and continued under the leadership of

Bird after his move from Arizona to Stanford, with further expeditions

in 1982 and most subsequent years. This work began to look at the hydrothermal

effects in the cooling Skaergaard body, work which was subsequently extended

to other intrusions and into other areas, but up to that time had been

largely ignored but for the stable isotopic work of Hugh Taylor. In association

with Bird, Charles E. Lesher of the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory

(now at the University of California, Davis) and Minik Rosing (Copenhagen)

began work on the Mikis Fjord Macrodyke to elucidate the interactions with

country rock, a question of great importance in Skaergaard (the macrodykes

where formed from very similar or even identical magmas to Skaergaard).

At the same time Craig White and Dennis Geist of the University of Idaho,

Boise, worked on the adjacent Vandfaldsdalen macrodike.

In 1988 parties from Copenhagen, Stanford, Oregon, Boise (Idaho) and

Binghamton (New York) were again in the field. H.R. (Dick) Naslund (Binghamton)

and the University of Copenhagen continued in 1989, and the University

of Copenhagen accompanied by T. Neil Irvine Geophysical Laboratory, Washington

D.C., continued in 1990 and 1991.

Distinguished

scientists who have visited the area are: Professor A. Noe-Nygaard of Copenhagen,

the "grand old man" of Danish geology (in 1986, when he was 80 years old),

and H.T. Tazieff, the celebrated French volcanologist and adventurer, in

1988. In 1990 a group of Icelandic geologists spent 1 week on the intrusion

and a party of distinguished international petrologists (A. Nicolas, A.

Boudreau, S. McCallum, I. Parsons, J. Wolff & R.St.J. Lambert) travelling

with A.R. McBirney spent somewhat longer. Perhaps these are the harbingers

of an accelerated tourism and in 1991, Kangerlussuaq was visited by an

expedition led by the celebrated mountaineer Chris Bonington and the equally

celebrated yachtsman Sir Robin Knox-Johnston in the yacht "Suhaili", which

spent several weeks in an anchorage at the entrance to Uttentals Sund (Bonington

& Knox-Johnston, 1992) and in subsequent years further parties of adventurers

have put in an appearance.

Distinguished

scientists who have visited the area are: Professor A. Noe-Nygaard of Copenhagen,

the "grand old man" of Danish geology (in 1986, when he was 80 years old),

and H.T. Tazieff, the celebrated French volcanologist and adventurer, in

1988. In 1990 a group of Icelandic geologists spent 1 week on the intrusion

and a party of distinguished international petrologists (A. Nicolas, A.

Boudreau, S. McCallum, I. Parsons, J. Wolff & R.St.J. Lambert) travelling

with A.R. McBirney spent somewhat longer. Perhaps these are the harbingers

of an accelerated tourism and in 1991, Kangerlussuaq was visited by an

expedition led by the celebrated mountaineer Chris Bonington and the equally

celebrated yachtsman Sir Robin Knox-Johnston in the yacht "Suhaili", which

spent several weeks in an anchorage at the entrance to Uttentals Sund (Bonington

& Knox-Johnston, 1992) and in subsequent years further parties of adventurers

have put in an appearance.

In 2000, a new gravity survey was carried out by C.K. Brooks and M.B.

Kristensen and a comprehensive new collection of hand samples was made

under the Danish Lithosphere Centre, while the existing cores were shipped

back to the Geological Museum, University of Copenhagen.

Commercial activity

In 1986, Platinova Resources Ltd. of Toronto (subsequently to be registered

in Nuuk/Godthåb, Greenland), under the active leadership of its president,

Mr. R.A. Gannicott, began exploration of the area with a view to

evaluating it for precious metal deposits - an interest inspired by the

published work of the Copenhagen group and the recently established logistic

facilities. During this first expedition, interest was aroused in Skaergaard,

largely as a result of geochemical prospecting, by Platinova and the Greenland

Geological Survey (Brooks et al., 1987). More comprehensive work

was done in 1987 and 1988 from a helicopter camp in Sødalen. In

1987 gold anomalies were found at several localities close to the Triple

Group (upper part of the Middle Zone). These showings were sampled in more

detail by climbers in 1988 with very promising results. This work showed

significant quantities of gold, associated with sulphides occurring in

particles up to 40m in size, along with electrum (Bird et al., 1991). The

gold can readily be separated by flotation. However its genesis is at present

unknown and the work has shown complications at this level in the intrusion

which call for new detailed studies. Comprehensive drilling was carried

out in 1989 and 1990, during which time an important Pd-rich zone was discovered

about 20 metres below the gold zone.

During the period 1986 to 1991, the mineral exploration activity,

referred to above, was in full swing and 16,600 metres of diamond drill-core

from 27 holes and 7 wedge cuts had been taken.and long runs of channel

and chip samples were recovered. This confirmed that mineralization was

continuous over an area of about 15 square kilometres or about 60% of the

area defined by surface mineralization. Resource estimates were calculated

by the Canadian firm of Watts, Griffis and McOuat Limited using a two metre

average width for the gold zone with a specific gravity of 3.23 as approximately

28,000,000 tons grading 2.5 grams/ton at a cut-off grade of 2.20 grams/ton,

which is raised to around 43,000,000 tons grading 2.38 grams/ton at a cut-off

grade of 2.0 grams/ton. The global estimate is that there are over 5 million

ounzes Au , which is a large deposit by any standards. In addition there

are significant quantities of palladium, platinum, copper and titanium:

valuable co-products, which could contribute significantly to the operation.

No estimates have been made of the value of the underlying palladium-rich

horizon at this time, but it underlies a similar area and is 3 to 6 metres

thick with an average of about 2 gm/tonne Pd. These figures are quoted

from the 1993 Annual Report to Shareholders of Platinova Ltd. and seem

to indicate amounts of as much as 50 m. oz.

This major gold find was first reported in the Danish newspaper Jyllandsposten

(Nov. 13th) by C.K. Brooks which led in the following days to a globally

extensive media coverage. The economic aspects were described briefly by

Brooks (1990) and by Nielsen (1990) and Nielsen & Schønwandt

(1990). The first scientific note was published in Economic Geology

(Bird et al. 1991). In late 1990 new excitment surfaced in the media with

the reported discovery of promising amounts of precious metals in the nearby

Kap Edvard Holm gabbro (Bird et al., 1995) and although by 1993 commercial

activity in the area had ceased, it is clear that it is only a matter of

time before the prospectors return. The deposit has been evaluated to be

marginal and gold prices have been low throughout the 90s. However other

precious metals have increased markedly in value due to their use in autocatalysators.

Thus, by 2001 the price of palladium had risen 10-fold to over $1000 per

ounce.

There is little doubt that the gold find will also lead to a greatly

increased scientific interest and the large amount of high quality drill-core

material available for this reseach is, as yet, virtually untapped. The

drill holes have also been used as holes of convenience in a heat flow

study by the universities of Copenhagen and Århus (at present unpublished).

Trends in Skaergaard research

Skaergaard research falls into four distinct phases: mapping and general

description of the intrusion in the 1930s; more detailed laboratory work

, largely geochemistry, in the 1950s and '60s; renewed fieldwork followed

by new interpretations in the 1970s and early 1980s; discovery of precious

metals and drilling in the late 1980s. In the 1990s, it is not easy to

discern which direction research is taking, proceeding on many fronts.

The 1930's saw the early work on the intrusion, it was mapped, its salient

features described and hypotheses presented to explain the origin of these

features. At this time, the main thrust was to explaining the "normal"

trend of igneous fractionation and resolving the Bowen-Fenner controversy

as to whether such fractionation produced granitic end products or led

to a trend of iron enrichment. Wager & Deer's work (Wager & Deer,

1939) achieved instant acclaim as it was the most detailed study of a gabbro

body available. Their work showed that under the conditions prevailing

in the Skaergaard magma chamber the trend was one of iron enrichment and

only negligible amounts of granite were generated.

During the 1950s and '60s, ideas of crystal settling were refined, but

above all this period saw a wealth of information on the behaviour of a

great number of elements during fractionation of a basaltic magma. In addition,

some early isotopic information was published. To this end Wager and his

co-workers, notably R.L. Mitchell and E.A. Vincent, began to work with

new analytical methods - first optical spectroscopy, later neutron activation

and mass spectrometry - that were to become of central importance in petrology

in the 1960s and '70s, especially in connection with newly acquired samples

from the moon and deep oceans. As these new methods were often first applied

to Skaergaard rocks and minerals, Skaergaard research laid the foundations

of much of what was to come in petrological advances. Wager did not concern

himself with experimental methods, but always insisted that his group observed

Nature and drew their conclusions from these observations, rather than

indulging in experimental petrology which was very much in vogue at the

time.

The 1970s and '80s saw, to a large extent, a return to the type of research

of the 1930's - field observations and their interpretation in the light

of current theoretical ideas. When being presented with the N.L. Bowen

Award of the American Geophysical Union in 1990, A.R. McBirney had this

to say about his first visit to Skaergaard (McBirney, 1991): "When I first

visited that magnificent place in 1971, I was sad that Wager had left so

little for us to explain. All I could contribute to his elegant account

of differentiation by crystal fractionation would be a bit more evidence

in support of the obvious. Now 20 years later, look where we are. We have

taken the intrusion apart and scrutinized it in great detail. We've mapped

it, run geophysical surveys, analysed it for every element and isotope

conceivable, and what do we have? Most people would say a shambles". In

short, McBirney was telling his audience that, in spite of all the effort,

understanding of the precise processes which had formed Skaergaard are

still very imperfectly known.

The '70s and '80s, were the decades when the original interpretations

were questioned: what is the form of the intrusion? - had crystals really

sunk in the magma? - what is the real differentiation trend? - and what

is the extent of sub-solidus alteration? Concepts of fluid dynamics came

to the forefront, and obscure minor elements were relegated to the back

seat. Interestingly, enough in the late '80s there was a tendency for return

to Wager & Deer's original ideas - McBirney (1985) questioned the idea

of double-diffusive convection (originally proposed by McBirney & Noyes,

1979) and a number of authors (McBirney & Naslund, 1990; Morse, 1990;

Brooks & Nielsen, 1990) championed the compositional trend proposed

by Wager & Deer but rejected by Hunter & Sparks (1987). These points

of view are still apparantly unsettled.

The late 1980s and early '90s are marked by a renewed interest in the

intrusion, sparked by the discovery of precious metals. Oddly enough Skaergaard

rocks were some of the earliest to be analysed for trace amounts of gold,

silver and palladium (Vincent & Smales, 1956; Vincent & Crocket,

1960; Adams, 1961), while Wager, Vincent & Smales (1957) in their study

of sulphides in Skaergaard made a very important contribution to our understanding

of orthomagmatic ore deposits. None of these authors suspected that the

intrusion might one day turn out to host a world class precious metals

deposit.

In the near future, we can perhaps expect an increased use of geophysics

to delineate the sub-surface parts of the intrusion, increased use of microbeam

techniques to acquire elemental and isotopic data on a microscale, greater

attention to the role of fluids and new detailed studies of the stratigraphic

variations. Newcomers to Skaergaard are frequently amazed to find just

how few samples have actually been studied. This situation will doubtless

change with the availability of many kilometres of diamond drill core.

In the citation of McBirney quoted above, he goes on to say:

"I think it is great to see so many entrenched ideas being challenged.

It was impossible to make any headway until we rid ourselves of a lot of

cherished beliefs. As a result, we can now start putting the pieces back

together and I am confident that we are gradually seeing our way out".

In a recent review of magmatic differentiation, Wilson (1993) made clear

the overwhelming importance of the Skaergaard studies to the development

of ideas and our understanding of the differentiation of basic magmas.

For example she writes: "The Skaergaard intrusion, east Greenland, has,

for the past 50 years been cited as the classic example of in-situ differentiation

of basic magma" and goes on to show that the evidence, which continues

to accumulate, is by no means unequivocal and we are still a long way from

achieving a consensus in exactly how to interpret this evidence.

This compilation represents the pieces, fundamental to igneous petrology,

which now wait to be put together, along with the data yet to be gathered.

Figure references

Mathiassen, T., 1935. Skrælingerne i Grønland. Udvalget

for Folkeoplysnings Fremme. 140 pages.

Mikkelsen, E., 1934. De østgrønlandske eskimoers historie.

Gyldendal.

202 pages. Photos by M. Spender and U.M. Hansen.

© 2003 skaergaard.org

To

the Ammassalik people, Kangerlussuaq apparently has always been regarded

as an especially rich hunting ground - a kind of Shangri-La, that can be

reached only with difficulty but where life can be expected to be good.

At the time of Gustav Holm, an umiak or family boat left Ammassalik

for Kangerlussuaq, but was never heard of again, and this expedition was

probably the origin of the corpses found in the house at Nugalik or Dødemandspynten

(="Dead Man's Point"), about 100 km to the south, found by Amdrup some

30 years later (Amdrup, 1902). The Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East

Greenland Expedition was largely motivated by the expressed desire of the

Ammassalik people to colonize Kangerlussuaq. Ammassalik people still regard

the area with high esteem: some as pragmatists who realize that they can

apply their hunting skills here with the prospect of improving their income,

others as idealists who see the area as a retreat from the white man's

world to the ways of their forefathers, untrammelled by money, stores,

officials, drunkenness and the like.

To

the Ammassalik people, Kangerlussuaq apparently has always been regarded

as an especially rich hunting ground - a kind of Shangri-La, that can be

reached only with difficulty but where life can be expected to be good.

At the time of Gustav Holm, an umiak or family boat left Ammassalik

for Kangerlussuaq, but was never heard of again, and this expedition was

probably the origin of the corpses found in the house at Nugalik or Dødemandspynten

(="Dead Man's Point"), about 100 km to the south, found by Amdrup some

30 years later (Amdrup, 1902). The Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East

Greenland Expedition was largely motivated by the expressed desire of the

Ammassalik people to colonize Kangerlussuaq. Ammassalik people still regard

the area with high esteem: some as pragmatists who realize that they can

apply their hunting skills here with the prospect of improving their income,

others as idealists who see the area as a retreat from the white man's

world to the ways of their forefathers, untrammelled by money, stores,

officials, drunkenness and the like.

These

Europeans - of the Amdrup-Hartz expedition, or even unknown European whalers

who may have landed here earlier without leaving a record - were by no

means the first people in this area. Indeed, Kangerlussuaq was a milepost

for the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition because it marked the northernmost point

known to the Ammassalik people (Ammassalimiut) as told to their discoverer

Gustav Holm in 1882 (Gustav Holm, 1888, 1889). Although no people lived

in the area at the turn of the century, numerous ruins of earlier dwellings

testify to the previous presence of the Inuit people. Indeed, an old man,

Kunak, told Gustav Holm that he had been born on the nearby island of Nordre

Aputitêq ( - new spelling: Apulileeq) and had travelled to Kangerlussuaq

in his youth. Material returned by the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition was described

by W. Thalbitzer (1909, see also Thalbitzer, 1914) and excavations on the

house ruins at Skærgård and in Miki Fjord where made by the

Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition in 1932 (Mathiassen,

1934; Degerbøl, 1934) and the Anglo-Danish East Greenland Expedition

of 1935 (Larsen, 1938). Since 1935 only minor archaeological work has been

carried out, in spite of the fact that revolutionary changes have taken

place in the field of Eskimo archaeology.

These

Europeans - of the Amdrup-Hartz expedition, or even unknown European whalers

who may have landed here earlier without leaving a record - were by no

means the first people in this area. Indeed, Kangerlussuaq was a milepost

for the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition because it marked the northernmost point

known to the Ammassalik people (Ammassalimiut) as told to their discoverer

Gustav Holm in 1882 (Gustav Holm, 1888, 1889). Although no people lived

in the area at the turn of the century, numerous ruins of earlier dwellings

testify to the previous presence of the Inuit people. Indeed, an old man,

Kunak, told Gustav Holm that he had been born on the nearby island of Nordre

Aputitêq ( - new spelling: Apulileeq) and had travelled to Kangerlussuaq

in his youth. Material returned by the Amdrup-Hartz Expedition was described

by W. Thalbitzer (1909, see also Thalbitzer, 1914) and excavations on the

house ruins at Skærgård and in Miki Fjord where made by the

Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition in 1932 (Mathiassen,

1934; Degerbøl, 1934) and the Anglo-Danish East Greenland Expedition

of 1935 (Larsen, 1938). Since 1935 only minor archaeological work has been

carried out, in spite of the fact that revolutionary changes have taken

place in the field of Eskimo archaeology.

Recent

endeavours to colonize Kangerlussuaq date from 1966 when a number of families

from Ammassalik (Tasiilaq) overwintered in the remains of the old American

weather station and the expedition houses from the 30s. They had a very

good season (- 35 bears, 62 narwhales and about 2100 seals) and returned

most years afterwards. Not surprisingly, many from Ammassalik find life

at Kangerlussuaq difficult and yearn for home, but others return year after

year. An excellent study of present social conditions among the Ammassalimiut

has been presented by Robert-Lamblin (1986), who recorded the numbers of

hunters at various sites along the coast up to 1979. In recent years the

number of people living at Kangerlussuaq was: 56(20) in 1986-87 (after

a hiatus of three years), 94(37) in 1987-88, 39 (16) in 1988-89, 0 in 1989-90

and 18(9) in 1990-91. In each case the first number is the total number

of individuals and the second (in brackets) the number of children under

16 years. Figures are based on data from Tasiilaq local council.

Recent

endeavours to colonize Kangerlussuaq date from 1966 when a number of families

from Ammassalik (Tasiilaq) overwintered in the remains of the old American

weather station and the expedition houses from the 30s. They had a very

good season (- 35 bears, 62 narwhales and about 2100 seals) and returned

most years afterwards. Not surprisingly, many from Ammassalik find life

at Kangerlussuaq difficult and yearn for home, but others return year after

year. An excellent study of present social conditions among the Ammassalimiut

has been presented by Robert-Lamblin (1986), who recorded the numbers of

hunters at various sites along the coast up to 1979. In recent years the

number of people living at Kangerlussuaq was: 56(20) in 1986-87 (after

a hiatus of three years), 94(37) in 1987-88, 39 (16) in 1988-89, 0 in 1989-90

and 18(9) in 1990-91. In each case the first number is the total number

of individuals and the second (in brackets) the number of children under

16 years. Figures are based on data from Tasiilaq local council.

Wager's

first visit to Skaergaard was of necessity brief, but he returned in 1932

as a member of the Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition

in 1932 (Mikkelsen,1933a & b). This committee had been formed to promote

the establishment of a settlement at Scoresby Sund (now Ittoqqortoormiit)

to relieve the population pressure at Ammassalik and in 1925 (as a result

of their first expedition) this settlement became a reality (Mikkelsen,

1927). The 1932 expedition was designed to explore the coastline

between Ammassalik and Scoresbysund and to erect houses at strategic points

along the coast, with a view to promoting travel between the two areas

and to explore the possibility for colonizing the Kangerlussuaq area. Although

the expedition was successful, its ultimate aim has never been fulfilled:

no journeys have ever been made by Inuit along the entire length of this

coast and no permanent settlement was ever established, although overwintering

parties have been at Skaergaard most years since 1966 (see above).

Wager's

first visit to Skaergaard was of necessity brief, but he returned in 1932

as a member of the Scoresby Sound Committee's 2nd East Greenland Expedition

in 1932 (Mikkelsen,1933a & b). This committee had been formed to promote

the establishment of a settlement at Scoresby Sund (now Ittoqqortoormiit)

to relieve the population pressure at Ammassalik and in 1925 (as a result

of their first expedition) this settlement became a reality (Mikkelsen,

1927). The 1932 expedition was designed to explore the coastline

between Ammassalik and Scoresbysund and to erect houses at strategic points

along the coast, with a view to promoting travel between the two areas

and to explore the possibility for colonizing the Kangerlussuaq area. Although

the expedition was successful, its ultimate aim has never been fulfilled:

no journeys have ever been made by Inuit along the entire length of this

coast and no permanent settlement was ever established, although overwintering

parties have been at Skaergaard most years since 1966 (see above).

A

long-standing Norwegian interest in the area led to the establishment of

a radio station, known as "Storfjord Radio", at Mudderbugt on the west

side of Kangerlussuaq (which is known to Norwegians as "Storfjord", the

Scandinavian translation of the Greenlandic name) as part of the International

Polar Year. This station operated through 1932-33 and remains can still

be seen. Several small huts were also erected around the fjord: at Spækpynten,

Bagnæsset and Skåret (on Kræmer Ø), for use by

sealers and shark fishers from Ålesund and Tromsø, but falling

prices for animal oils, the main product of this industry, led to their

abandonment in the 1950s. The characteristic wooden ships (Signalhorn,

Furenak, Brandal, Polarbjørn) which were mostly built around

the turn of the century, have now disappeared from the area, but their

immense strength and the unparalleled skill of their skippers in these

treacherous waters meant that a few of them were still in demand as expedition

ships and supply vessels for the weather stations such as Nordre Apulileeq

(= Aputitêq), where seven men lived totally isolated except for the

yearly ship. Many Skaergaard geologists will remember the cheerful stewards

on these ships, with their filling Norwegian food, after a summer on meagre

expedition rations. They will similarly remember how the ships, built for

shunting ice, rolled in the autumn swell of the Denmark Strait and how

quickly the desire to visit the mess-room disappeared. These ships are

now all gone. Commercial sealing has virtually ceased due to the pressures

of the environmental lobby; geologists now fly and the weather station

at Nordre Apulileeq was closed in 1979 due to financial restrictions and

the introduction of automatic, telemetred weather reporting. Since that

time, the once luxurious facilities at the station have fallen into a ruinous

condition. Until recently the only ship visiting Skaergaard was Ejnar Mikkelsen,

the local boat from Ammassalik, chartered by the municipality (Tasiilaq

Kommune) to transport the hunters, their families, dogs and equipment.

Its skipper, Hans Ignatiussen, was a son of one of the couples who pioneered

the present overwintering parties at Skaergaard. However, in connection

with mineral exploration (see below), Icelandic boats (including an old

roll-on-roll-off car ferry) have been chartered in recent years to deliver

fuel for diamond drilling and helicopters and the Ejnar Mikkelsen is no

more, having been destroyed by the ice in the winter of 1993.

A

long-standing Norwegian interest in the area led to the establishment of

a radio station, known as "Storfjord Radio", at Mudderbugt on the west

side of Kangerlussuaq (which is known to Norwegians as "Storfjord", the

Scandinavian translation of the Greenlandic name) as part of the International

Polar Year. This station operated through 1932-33 and remains can still

be seen. Several small huts were also erected around the fjord: at Spækpynten,

Bagnæsset and Skåret (on Kræmer Ø), for use by

sealers and shark fishers from Ålesund and Tromsø, but falling

prices for animal oils, the main product of this industry, led to their

abandonment in the 1950s. The characteristic wooden ships (Signalhorn,

Furenak, Brandal, Polarbjørn) which were mostly built around

the turn of the century, have now disappeared from the area, but their

immense strength and the unparalleled skill of their skippers in these

treacherous waters meant that a few of them were still in demand as expedition

ships and supply vessels for the weather stations such as Nordre Apulileeq

(= Aputitêq), where seven men lived totally isolated except for the

yearly ship. Many Skaergaard geologists will remember the cheerful stewards

on these ships, with their filling Norwegian food, after a summer on meagre

expedition rations. They will similarly remember how the ships, built for

shunting ice, rolled in the autumn swell of the Denmark Strait and how

quickly the desire to visit the mess-room disappeared. These ships are

now all gone. Commercial sealing has virtually ceased due to the pressures

of the environmental lobby; geologists now fly and the weather station

at Nordre Apulileeq was closed in 1979 due to financial restrictions and

the introduction of automatic, telemetred weather reporting. Since that

time, the once luxurious facilities at the station have fallen into a ruinous

condition. Until recently the only ship visiting Skaergaard was Ejnar Mikkelsen,

the local boat from Ammassalik, chartered by the municipality (Tasiilaq

Kommune) to transport the hunters, their families, dogs and equipment.

Its skipper, Hans Ignatiussen, was a son of one of the couples who pioneered

the present overwintering parties at Skaergaard. However, in connection

with mineral exploration (see below), Icelandic boats (including an old

roll-on-roll-off car ferry) have been chartered in recent years to deliver

fuel for diamond drilling and helicopters and the Ejnar Mikkelsen is no

more, having been destroyed by the ice in the winter of 1993.

After

1953, another long hiatus in field work ensued, but during this period

a large amount of laboratory work was published, dealing especially with

the geochemistry of numerous trace elements. Apart from a brief visit by

J.A.V.Douglas in 1962, no geologist came to Skaergaard again until 1966,

when there was a new British East Greenland Geological Expedition (Deer,

1967). The main purpose of this expedition was to sample the intrusion

by several diamond drill holes: a deep hole in the Hidden Zone and several

shorter holes specifically aimed at studying sedimentation phenomena in

the exposed layered series. In addition, several of the other Tertiary

intrusive centres were to be explored, notably the Kappa Edward Hole, and

Lilies areas. The impetus for deep drilling came from the "MO hole"

project: Wager had been to California, attending a meeting of the International

Mineralogical Association, where there was a session on layered intrusions.

This was the time of the ill-fated "MO hole" project, while a plan was

also afoot to drill the Muskox intrusion by the Geological Survey of Canada

(realized in 1964) and Wager came to consider the possibility of using

a drilling barge at Skaergaard. This turned out to be impractical, but

it sparked the interest in drilling and an expedition was planned to extend

over two years. However, when Wager died in the later part of 1965, while

heavily involved in preparations for the expedition, the leadership passed

to W.A.Deer and for various reasons the project was shortened to only one

year. The sedimentation study had been Wager's special interest and no-one

was forthcoming with sufficient enthusiasm to take it over and it was dropped.

Also, the original drilling plan for the Hidden Zone proved too ambitious

without considerably escalating the cost of the expedition. Thus after

a 349 m hole had been drilled at a site on the eastern shore of Uttentals

Sund, starting in the lowest part of the Lower Zone, a second hole of 150

m was drilled at another site on the shore just south of Forbindelsesgletscher,

penetrating into the Triple Group. The drill used was a Longyear 35 and

core recovery was very high. Several additional holes were drilled to 45

m along a single stratigraphic interval using a "Packsack" drill with a

motorized hoist, and about two dozen holes, 5 m deep were drilled in the

Trough Bands with a "Dinky" drill. In all 588 m (1930 feet) of core were

recovered and has since been stored at the Department of Earth Sciences

in Cambridge. Up until the present time, the only studies which have been

made of this material were by Maaløe (1974, 1976, 1978, 1987), Nwe

(1975, 1976) and Nwe & Copely (1975). The drilling programme did not

really live up to expectations in that only about 150 m of the Hidden Zone

were penetrated (according to Wager's estimates it is as much as 5 km in

thickness) owing to the loss of water from the drill at this depth and

indications that the hole was passing out of the intrusion. The sedimentation

study visualized by Wager was not carried out, although drill cores for

this purpose were obtained. It was ironic that the major hole into the

Triple Group penetrated to the stratigraphic zone that was later identified

as being gold-bearing, but presence of this zone was not realized at the

time.

After

1953, another long hiatus in field work ensued, but during this period

a large amount of laboratory work was published, dealing especially with

the geochemistry of numerous trace elements. Apart from a brief visit by

J.A.V.Douglas in 1962, no geologist came to Skaergaard again until 1966,

when there was a new British East Greenland Geological Expedition (Deer,

1967). The main purpose of this expedition was to sample the intrusion

by several diamond drill holes: a deep hole in the Hidden Zone and several

shorter holes specifically aimed at studying sedimentation phenomena in

the exposed layered series. In addition, several of the other Tertiary

intrusive centres were to be explored, notably the Kappa Edward Hole, and

Lilies areas. The impetus for deep drilling came from the "MO hole"

project: Wager had been to California, attending a meeting of the International

Mineralogical Association, where there was a session on layered intrusions.

This was the time of the ill-fated "MO hole" project, while a plan was

also afoot to drill the Muskox intrusion by the Geological Survey of Canada

(realized in 1964) and Wager came to consider the possibility of using

a drilling barge at Skaergaard. This turned out to be impractical, but

it sparked the interest in drilling and an expedition was planned to extend

over two years. However, when Wager died in the later part of 1965, while

heavily involved in preparations for the expedition, the leadership passed

to W.A.Deer and for various reasons the project was shortened to only one

year. The sedimentation study had been Wager's special interest and no-one

was forthcoming with sufficient enthusiasm to take it over and it was dropped.

Also, the original drilling plan for the Hidden Zone proved too ambitious

without considerably escalating the cost of the expedition. Thus after

a 349 m hole had been drilled at a site on the eastern shore of Uttentals

Sund, starting in the lowest part of the Lower Zone, a second hole of 150

m was drilled at another site on the shore just south of Forbindelsesgletscher,

penetrating into the Triple Group. The drill used was a Longyear 35 and

core recovery was very high. Several additional holes were drilled to 45

m along a single stratigraphic interval using a "Packsack" drill with a

motorized hoist, and about two dozen holes, 5 m deep were drilled in the

Trough Bands with a "Dinky" drill. In all 588 m (1930 feet) of core were

recovered and has since been stored at the Department of Earth Sciences

in Cambridge. Up until the present time, the only studies which have been

made of this material were by Maaløe (1974, 1976, 1978, 1987), Nwe

(1975, 1976) and Nwe & Copely (1975). The drilling programme did not

really live up to expectations in that only about 150 m of the Hidden Zone

were penetrated (according to Wager's estimates it is as much as 5 km in

thickness) owing to the loss of water from the drill at this depth and

indications that the hole was passing out of the intrusion. The sedimentation

study visualized by Wager was not carried out, although drill cores for

this purpose were obtained. It was ironic that the major hole into the

Triple Group penetrated to the stratigraphic zone that was later identified

as being gold-bearing, but presence of this zone was not realized at the

time.

Distinguished

scientists who have visited the area are: Professor A. Noe-Nygaard of Copenhagen,

the "grand old man" of Danish geology (in 1986, when he was 80 years old),

and H.T. Tazieff, the celebrated French volcanologist and adventurer, in

1988. In 1990 a group of Icelandic geologists spent 1 week on the intrusion

and a party of distinguished international petrologists (A. Nicolas, A.

Boudreau, S. McCallum, I. Parsons, J. Wolff & R.St.J. Lambert) travelling

with A.R. McBirney spent somewhat longer. Perhaps these are the harbingers

of an accelerated tourism and in 1991, Kangerlussuaq was visited by an

expedition led by the celebrated mountaineer Chris Bonington and the equally

celebrated yachtsman Sir Robin Knox-Johnston in the yacht "Suhaili", which

spent several weeks in an anchorage at the entrance to Uttentals Sund (Bonington

& Knox-Johnston, 1992) and in subsequent years further parties of adventurers

have put in an appearance.

Distinguished

scientists who have visited the area are: Professor A. Noe-Nygaard of Copenhagen,

the "grand old man" of Danish geology (in 1986, when he was 80 years old),

and H.T. Tazieff, the celebrated French volcanologist and adventurer, in

1988. In 1990 a group of Icelandic geologists spent 1 week on the intrusion

and a party of distinguished international petrologists (A. Nicolas, A.

Boudreau, S. McCallum, I. Parsons, J. Wolff & R.St.J. Lambert) travelling

with A.R. McBirney spent somewhat longer. Perhaps these are the harbingers

of an accelerated tourism and in 1991, Kangerlussuaq was visited by an

expedition led by the celebrated mountaineer Chris Bonington and the equally

celebrated yachtsman Sir Robin Knox-Johnston in the yacht "Suhaili", which

spent several weeks in an anchorage at the entrance to Uttentals Sund (Bonington

& Knox-Johnston, 1992) and in subsequent years further parties of adventurers

have put in an appearance.